The Inverted Yield Curve

A Dog that Didn’t Bark?

Paul Samuelson once famously quipped that the stock market has predicted nine of the last five recessions. The bond market on the other hand is more reliable. Financial analysts closely watch the yield curve, measured by the spread between long-term interest rates and short-term rates, because an inverted yield curve (i.e., a negative spread) seems to predict a looming recession.

The New York Fed even maintains a website called The Yield Curve as a Leading Indicator.

The latest inversion in 2022, however, did not follow the script. This post explains why.

The Fed controls the interest rate on overnight loans through its enormous balance sheet. This policy rate has a strong effect on other short-term rates, out to the one- or two-year window.

Normally, the spread between long and short rates is positive. Asset managers require a higher yield on bonds with longer maturity. When the yield curve inverts, the spread becomes negative. Bonds with shorter maturity earn higher returns than those with a long maturity.

In the U.S., yield curve inversions correctly anticipated every recession in the last 70 years. There was one brief false positive in 1966, which reversed itself quickly.

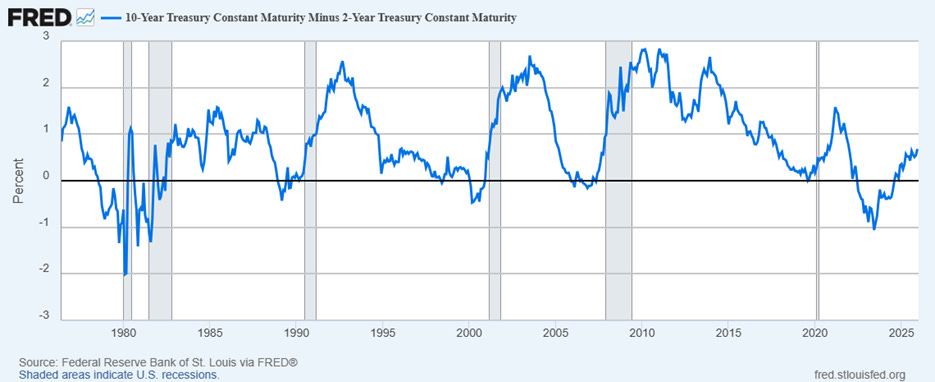

The figure below from FRED Data shows one of the most-used metrics for the yield curve, the spread between 10-year U.S. Treasuries and 2-year Treasuries. The gray bars represent recessions and in every case before the Covid recession these follow an inversion. (The data start in 1976, so you will have to take my word that aside from 1966, inversions preceded recessions in the years prior to that.)

It goes without saying that the brief and tiny inversion that preceded the Covid recession is meaningless. No one thinks the financial markets are clairvoyant epidemiologists!

From mid-2022 to 2024, the yield curve for U.S. Treasuries inverted rather convincingly, yet the recession that should have followed the historical pattern failed to materialize. Was this an example of Sherlock Holmes’s famous “dog that didn’t bark?”

In a paper with Leila Davis, we argue that the yield curve no longer functions as a reliable portent of impending recession because the inflation process has become anchored and the Fed has room to avoid using unemployment to combat inflation.

The underlying theory of the yield curve that explains why it portends a recession is based on the expectations hypothesis. The idea is that it is possible to create a synthetic bond with a long maturity by buying a short-maturity bond and then rolling it over. For example, a series of five 2-year Treasuries rolled over consecutively is equivalent to buying a 10-year bond and holding it till maturity.

As a result, all else equal, the return on a long bond should be equal to the average of the expected returns on the five short bonds in this example. This is a basic no-arbitrage condition. If it were violated, investors would be able to profit by taking a long position in the high-return bond and shorting the low-return bond.

Of course, all else is never equal in the world of economics and finance. There is also a “term premium” on longer dated bonds. Typically this is positive but in the low-interest period after 2008 was often observed to be negative. The expectations hypothesis does a miserable job of predicting interest rates because the term premium is variable and poorly understood. I certainly don’t claim to understand it.

But that does not negate the central insight of the expectations hypothesis, which has been a fixture in macroeconomics for decades and has been embraced by Keynesians and neoclassical economists alike, not to mention practitioners. (I first learned it from Nicholas Kaldor’s writings.)

And the expectations hypothesis does a good job of explaining why the yield curve has anticipated post-war recessions in the U.S. The financial markets seem to have been watching the Fed closely for any signs of a tightening cycle designed to generate enough economic slack to combat a spike in the inflation rate.

If the Fed raises interest rates to choke off aggregate demand and effectively engineer a recession, it will almost certainly have to lower interest rates in the future to engineer a recovery. The expectations hypothesis suggests that long-term interest rates will go down now as the result of the future period of low interest rates needed for recovery.

In other words, the short-term rates that are controlled by the Fed will rise while the long-term rates that depend on expectations of future Fed policies will fall. The yield curve inverts.

This inversion will be predictive of recession if that is the Fed’s objective. And until recently, the Fed has found it necessary to use unemployment to combat inflation. That is why the yield curve proved to be such a reliable recession indicator.

The Fed has been responding to inflation in this way long before it adopted an explicit inflation target. Ray Fair, a careful econometrician who maintains a medium-scale model of the U.S. economy, has long held that the Fed obeys a predictable “reaction function” that is very similar to the modern Taylor Rule.

But as the previous post explained, the inflation process has become anchored. It is no longer necessary for the Fed to use unemployment to combat inflation, although their allegiance to the so-called Taylor Rule makes them lean in that direction.

The Fed has the option of looking through an inflation spike such as the Covid inflation of 2021. Although they did raise interest rates, they did not follow the Taylor Rule to the letter, and they failed to create significant economic slack (aka unemployment). The disinflation that followed the Covid spike was proof of concept for anchoring.

But as we show in our paper, if the Fed plans on maintaining aggregate demand at its inflation-neutral level after an inflation shock, it will still need to raise the nominal rate of interest that it controls.

The reason is that spending (especially on construction, which is interest-sensitive) depends on the inflation-adjusted or “real” interest rate. This is the nominal rate minus the expected inflation rate. The intuition is that inflation lets borrowers pay back loans in depreciated dollars.

As a result, to keep the real interest rate constant after an inflation spike requires an increase in the nominal interest rate.

Even if the Fed has chosen to avoid a recession after an inflation shock, they will still need to raise the policy interest rate, which in turn will raise short-term rates like those on 2-year Treasuries. But if inflation is anchored, it will come down on its own, and as it does the Fed will be obliged to lower nominal interest rates pari passu (Latin for “in step”).

By the same logic used above it is clear that the Fed’s actions in navigating an inflation spike without resorting to economic slack will also invert the yield curve. Bond investors will anticipate that the rise in the short-term interest rate will be followed by a period of declining rates as inflation works its way out of the system.

So what the dog’s silence is telling us is that the world has changed. Anchoring has created space for the Fed to avoid using unemployment to contain inflation.

Of course, the real world is not the same as a macroeconomic model, which is just a tool to help clarify our thoughts and understand the logic of the system. The Fed probably did not plan on a painless response to the Covid inflation spike, and in fact from their projections it is clear that they did expect their interest rate hikes to raise the unemployment rate along Taylor Rule lines. Fortunately for millions of working people, they miscalculated.

But the lessons of their miscalculation should not be lost on us. Controlling inflation at the expense of jobs has become a barbarous relic. And yield curve inversions just don’t mean what they used to.

This framing of the yield curve inversion as the dog that didn't bark is brilliant! The anchoring argument makes intuitive sense - I remember watching all the recession forecasts in 2023 confidently predicting a downturn that never materialized. What I dunno though is whether the anchoring mechanism itself might be somewhat fragile if the Fed's crediblity ever takes a serious hit. One posibility that worries me is whether this painless disinflation was partly lucky timing with supply chain normalizations, not just pure policy success.